Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

4 posters

Page 1 of 1

Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

In early March, British leaders planned to take a laissez-faire approach to the spread of the coronavirus. Officials would pursue “herd immunity,” allowing as many people in non-vulnerable categories to catch the virus in the hope that eventually it would stop spreading. But on March 16, a report from the Imperial College Covid-19 Response Team, led by noted epidemiologist Neil Ferguson, shocked the Cabinet of the United Kingdom into a complete reversal of its plans. Report 9, titled “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand,” used computational models to predict that, absent social distancing and other mitigation measures, Britain would suffer 500,000 deaths from the coronavirus. Even with mitigation measures in place, the report said, the epidemic “would still likely result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and health systems (most notably intensive care units) being overwhelmed many times over.” The conclusions so alarmed Prime Minister Boris Johnson that he imposed a national quarantine.

Subsequent publication of the details of the computer model that the Imperial College team used to reach its conclusions raised eyebrows among epidemiologists and specialists in computational biology and presented some uncomfortable questions about model-driven decision-making. The Imperial College model itself appeared solid. As a spatial model, it divides the area of the U.K. into small cells, then simulates various processes of transmission, incubation, and recovery over each cell. It factors in a good deal of randomness. The model is typically run tens of thousands of times, and results are averaged—a technique commonly referred to as an ensemble model.

In a tweet sent in late March, Ferguson—then still one of the leading voices within the U.K.’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), tasked with handling the coronavirus crisis—stated that the model was implemented in “thousands of lines of undocumented” code written in C, a widely used and high-performing computing language. He refused to publish the original source code, and Imperial College has refused a Freedom of Information Act request for the original source, alleging that the public interest is not sufficiently compelling.

As Ferguson himself admits, the code was written 13 years ago, to model an influenza pandemic. This raises multiple questions: other than Ferguson’s reputation, what did the British government have at its disposal to assess the model and its implementation? How was the model validated, and what safeguards were implemented to ensure that it was correctly applied? The recent release of an improved version of the source code does not paint a favorable picture. The code is a tangled mess of undocumented steps, with no discernible overall structure. Even experienced developers would have to make a serious effort to understand it.

I’m a virologist, and modelling complex processes is part of my day-to-day work. It’s not uncommon to see long and complex code for predicting the movement of an infection in a population, but tools exist to structure and document code properly. The Imperial College effort suggests an incumbency effect: with their outstanding reputations, the college and Ferguson possessed an authority based solely on their own authority. The code on which they based their predictions would not pass a cursory review by a Ph.D. committee in computational epidemiology.

Ferguson and Imperial College’s refusal of all requests to examine taxpayer-funded code that supported one of the most significant peacetime decisions in British history is entirely contrary to the principles of open science—especially in the Internet age. The Web has created an unprecedented scientific commons, a marketplace of ideas in which Ferguson’s arguments sound only a little better than “the dog ate my homework.” Worst of all, however, Ferguson and Imperial College, through both their work and their haughtiness about it, have put the public at risk. Epidemiological modelling is a valuable tool for public health, and Covid-19 underscores the value of such models in decision-making. But the Imperial College model implementation lends credence to the worst fears of modelling skeptics—namely, that many models are no better than high-stakes gambles played on computers. This isn’t true: well-executed models can contribute to the objective, data-driven decision-making that we should expect from our leaders in a crisis. But leaders need to learn how to vet models and data.

The first step toward integrating predictive models into evidence-based policy is thorough assessment of the models’ assumptions and implementation. Reasonable skepticism about predictive models is not unscientific—and blind trust in an untested, shoddily written model is not scientific. As Socrates might have put it, an unexamined model is not worth trusting.

https://www.city-journal.org/coronavirus-model-driven-decision-making

Interesting article in regards to how the British response changed so quickly. Of course I'm no expert on these things but the guy who wrote it seems like he may know a thing or two.

"Chris von Csefalvay is an epidemiologist specializing in bat-borne viruses. He is currently VP of Special Projects at Starschema."

Subsequent publication of the details of the computer model that the Imperial College team used to reach its conclusions raised eyebrows among epidemiologists and specialists in computational biology and presented some uncomfortable questions about model-driven decision-making. The Imperial College model itself appeared solid. As a spatial model, it divides the area of the U.K. into small cells, then simulates various processes of transmission, incubation, and recovery over each cell. It factors in a good deal of randomness. The model is typically run tens of thousands of times, and results are averaged—a technique commonly referred to as an ensemble model.

In a tweet sent in late March, Ferguson—then still one of the leading voices within the U.K.’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), tasked with handling the coronavirus crisis—stated that the model was implemented in “thousands of lines of undocumented” code written in C, a widely used and high-performing computing language. He refused to publish the original source code, and Imperial College has refused a Freedom of Information Act request for the original source, alleging that the public interest is not sufficiently compelling.

As Ferguson himself admits, the code was written 13 years ago, to model an influenza pandemic. This raises multiple questions: other than Ferguson’s reputation, what did the British government have at its disposal to assess the model and its implementation? How was the model validated, and what safeguards were implemented to ensure that it was correctly applied? The recent release of an improved version of the source code does not paint a favorable picture. The code is a tangled mess of undocumented steps, with no discernible overall structure. Even experienced developers would have to make a serious effort to understand it.

I’m a virologist, and modelling complex processes is part of my day-to-day work. It’s not uncommon to see long and complex code for predicting the movement of an infection in a population, but tools exist to structure and document code properly. The Imperial College effort suggests an incumbency effect: with their outstanding reputations, the college and Ferguson possessed an authority based solely on their own authority. The code on which they based their predictions would not pass a cursory review by a Ph.D. committee in computational epidemiology.

Ferguson and Imperial College’s refusal of all requests to examine taxpayer-funded code that supported one of the most significant peacetime decisions in British history is entirely contrary to the principles of open science—especially in the Internet age. The Web has created an unprecedented scientific commons, a marketplace of ideas in which Ferguson’s arguments sound only a little better than “the dog ate my homework.” Worst of all, however, Ferguson and Imperial College, through both their work and their haughtiness about it, have put the public at risk. Epidemiological modelling is a valuable tool for public health, and Covid-19 underscores the value of such models in decision-making. But the Imperial College model implementation lends credence to the worst fears of modelling skeptics—namely, that many models are no better than high-stakes gambles played on computers. This isn’t true: well-executed models can contribute to the objective, data-driven decision-making that we should expect from our leaders in a crisis. But leaders need to learn how to vet models and data.

The first step toward integrating predictive models into evidence-based policy is thorough assessment of the models’ assumptions and implementation. Reasonable skepticism about predictive models is not unscientific—and blind trust in an untested, shoddily written model is not scientific. As Socrates might have put it, an unexamined model is not worth trusting.

https://www.city-journal.org/coronavirus-model-driven-decision-making

Interesting article in regards to how the British response changed so quickly. Of course I'm no expert on these things but the guy who wrote it seems like he may know a thing or two.

"Chris von Csefalvay is an epidemiologist specializing in bat-borne viruses. He is currently VP of Special Projects at Starschema."

Maddog- The newsfix Queen

- Posts : 12532

Join date : 2017-09-23

Location : Texas

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Let’s set the stage here. At issue are two competing sides: on the one hand there is a scientific discipline, which has no personal interest; on the other hand, there is an economic concern, which has the special interests of investors and the motive of profit to drive it.

In between, are the workers, their families and loved ones—indeed, the entire middle/lower class—that have conflicting concerns of (a) life and health, over a concern to (b) earn a wage. While the investors/special interests have every leave to retreat to their yachts and summer homes to ride out these troubles, a win-win solution, the middle/lower class must post on the front lines and bolster up the economy, or stay at home, protect their health and lose their income, a lose-lose solution.

Comes now a specialist with a minor methodological complaint aimed at the scientists and their analysis, by an investor-oriented co-scientist (VP of Special Projects at Starschema), and suddenly the investors/special interests pick up the article and draw back their bow strings. Never mind that they know nothing of the subject, nor care about “codes” and “high-performing computing languages”. They care only that it criticizes the side standing 'twixt them and their profits.

Sometimes someone will characterize this debate as health vs. the economy or medical science vs. a paycheck, but those are frames only because the investor side gets to attach the labels. In practical terms, it’s lives vs. profit, never mind that the investors and their politicians have crafted the debate, and phoned it in from their yacht. The task-masters want the beasts-of-burden to go back to work for them, because their investments are nothing without workers.

The fact that this article dresses the issue up in methodological multisyllabic terms does nothing for the real debate. So what if the writer was denied access to ‘codes’. His point is being stolen by profit-takers to discredit science, when science has no interest except the general humanism that we all share.

In between, are the workers, their families and loved ones—indeed, the entire middle/lower class—that have conflicting concerns of (a) life and health, over a concern to (b) earn a wage. While the investors/special interests have every leave to retreat to their yachts and summer homes to ride out these troubles, a win-win solution, the middle/lower class must post on the front lines and bolster up the economy, or stay at home, protect their health and lose their income, a lose-lose solution.

Comes now a specialist with a minor methodological complaint aimed at the scientists and their analysis, by an investor-oriented co-scientist (VP of Special Projects at Starschema), and suddenly the investors/special interests pick up the article and draw back their bow strings. Never mind that they know nothing of the subject, nor care about “codes” and “high-performing computing languages”. They care only that it criticizes the side standing 'twixt them and their profits.

Sometimes someone will characterize this debate as health vs. the economy or medical science vs. a paycheck, but those are frames only because the investor side gets to attach the labels. In practical terms, it’s lives vs. profit, never mind that the investors and their politicians have crafted the debate, and phoned it in from their yacht. The task-masters want the beasts-of-burden to go back to work for them, because their investments are nothing without workers.

The fact that this article dresses the issue up in methodological multisyllabic terms does nothing for the real debate. So what if the writer was denied access to ‘codes’. His point is being stolen by profit-takers to discredit science, when science has no interest except the general humanism that we all share.

Original Quill- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 37540

Join date : 2013-12-19

Age : 59

Location : Northern California

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Maddog wrote:In early March, British leaders planned to take a laissez-faire approach to the spread of the coronavirus. Officials would pursue “herd immunity,” allowing as many people in non-vulnerable categories to catch the virus in the hope that eventually it would stop spreading. But on March 16, a report from the Imperial College Covid-19 Response Team, led by noted epidemiologist Neil Ferguson, shocked the Cabinet of the United Kingdom into a complete reversal of its plans. Report 9, titled “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand,” used computational models to predict that, absent social distancing and other mitigation measures, Britain would suffer 500,000 deaths from the coronavirus. Even with mitigation measures in place, the report said, the epidemic “would still likely result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and health systems (most notably intensive care units) being overwhelmed many times over.” The conclusions so alarmed Prime Minister Boris Johnson that he imposed a national quarantine.

Subsequent publication of the details of the computer model that the Imperial College team used to reach its conclusions raised eyebrows among epidemiologists and specialists in computational biology and presented some uncomfortable questions about model-driven decision-making. The Imperial College model itself appeared solid. As a spatial model, it divides the area of the U.K. into small cells, then simulates various processes of transmission, incubation, and recovery over each cell. It factors in a good deal of randomness. The model is typically run tens of thousands of times, and results are averaged—a technique commonly referred to as an ensemble model.

In a tweet sent in late March, Ferguson—then still one of the leading voices within the U.K.’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), tasked with handling the coronavirus crisis—stated that the model was implemented in “thousands of lines of undocumented” code written in C, a widely used and high-performing computing language. He refused to publish the original source code, and Imperial College has refused a Freedom of Information Act request for the original source, alleging that the public interest is not sufficiently compelling.

As Ferguson himself admits, the code was written 13 years ago, to model an influenza pandemic. This raises multiple questions: other than Ferguson’s reputation, what did the British government have at its disposal to assess the model and its implementation? How was the model validated, and what safeguards were implemented to ensure that it was correctly applied? The recent release of an improved version of the source code does not paint a favorable picture. The code is a tangled mess of undocumented steps, with no discernible overall structure. Even experienced developers would have to make a serious effort to understand it.

I’m a virologist, and modelling complex processes is part of my day-to-day work. It’s not uncommon to see long and complex code for predicting the movement of an infection in a population, but tools exist to structure and document code properly. The Imperial College effort suggests an incumbency effect: with their outstanding reputations, the college and Ferguson possessed an authority based solely on their own authority. The code on which they based their predictions would not pass a cursory review by a Ph.D. committee in computational epidemiology.

Ferguson and Imperial College’s refusal of all requests to examine taxpayer-funded code that supported one of the most significant peacetime decisions in British history is entirely contrary to the principles of open science—especially in the Internet age. The Web has created an unprecedented scientific commons, a marketplace of ideas in which Ferguson’s arguments sound only a little better than “the dog ate my homework.” Worst of all, however, Ferguson and Imperial College, through both their work and their haughtiness about it, have put the public at risk. Epidemiological modelling is a valuable tool for public health, and Covid-19 underscores the value of such models in decision-making. But the Imperial College model implementation lends credence to the worst fears of modelling skeptics—namely, that many models are no better than high-stakes gambles played on computers. This isn’t true: well-executed models can contribute to the objective, data-driven decision-making that we should expect from our leaders in a crisis. But leaders need to learn how to vet models and data.

The first step toward integrating predictive models into evidence-based policy is thorough assessment of the models’ assumptions and implementation. Reasonable skepticism about predictive models is not unscientific—and blind trust in an untested, shoddily written model is not scientific. As Socrates might have put it, an unexamined model is not worth trusting.

https://www.city-journal.org/coronavirus-model-driven-decision-making

Interesting article in regards to how the British response changed so quickly. Of course I'm no expert on these things but the guy who wrote it seems like he may know a thing or two.

"Chris von Csefalvay is an epidemiologist specializing in bat-borne viruses. He is currently VP of Special Projects at Starschema."

Interesting...

I would say that all of this computer modelling predictions are totally flawed for the simple reason that it was all based on the assumption that the virus didn't arrive here in UK until early February, and first transmission within the UK was believed to be near the end of February...

But the virus has been going around here in UK since before Christmas!

Tommy Monk- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 26319

Join date : 2014-02-12

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Tommy Monk wrote:Maddog wrote:In early March, British leaders planned to take a laissez-faire approach to the spread of the coronavirus. Officials would pursue “herd immunity,” allowing as many people in non-vulnerable categories to catch the virus in the hope that eventually it would stop spreading. But on March 16, a report from the Imperial College Covid-19 Response Team, led by noted epidemiologist Neil Ferguson, shocked the Cabinet of the United Kingdom into a complete reversal of its plans. Report 9, titled “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand,” used computational models to predict that, absent social distancing and other mitigation measures, Britain would suffer 500,000 deaths from the coronavirus. Even with mitigation measures in place, the report said, the epidemic “would still likely result in hundreds of thousands of deaths and health systems (most notably intensive care units) being overwhelmed many times over.” The conclusions so alarmed Prime Minister Boris Johnson that he imposed a national quarantine.

Subsequent publication of the details of the computer model that the Imperial College team used to reach its conclusions raised eyebrows among epidemiologists and specialists in computational biology and presented some uncomfortable questions about model-driven decision-making. The Imperial College model itself appeared solid. As a spatial model, it divides the area of the U.K. into small cells, then simulates various processes of transmission, incubation, and recovery over each cell. It factors in a good deal of randomness. The model is typically run tens of thousands of times, and results are averaged—a technique commonly referred to as an ensemble model.

In a tweet sent in late March, Ferguson—then still one of the leading voices within the U.K.’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), tasked with handling the coronavirus crisis—stated that the model was implemented in “thousands of lines of undocumented” code written in C, a widely used and high-performing computing language. He refused to publish the original source code, and Imperial College has refused a Freedom of Information Act request for the original source, alleging that the public interest is not sufficiently compelling.

As Ferguson himself admits, the code was written 13 years ago, to model an influenza pandemic. This raises multiple questions: other than Ferguson’s reputation, what did the British government have at its disposal to assess the model and its implementation? How was the model validated, and what safeguards were implemented to ensure that it was correctly applied? The recent release of an improved version of the source code does not paint a favorable picture. The code is a tangled mess of undocumented steps, with no discernible overall structure. Even experienced developers would have to make a serious effort to understand it.

I’m a virologist, and modelling complex processes is part of my day-to-day work. It’s not uncommon to see long and complex code for predicting the movement of an infection in a population, but tools exist to structure and document code properly. The Imperial College effort suggests an incumbency effect: with their outstanding reputations, the college and Ferguson possessed an authority based solely on their own authority. The code on which they based their predictions would not pass a cursory review by a Ph.D. committee in computational epidemiology.

Ferguson and Imperial College’s refusal of all requests to examine taxpayer-funded code that supported one of the most significant peacetime decisions in British history is entirely contrary to the principles of open science—especially in the Internet age. The Web has created an unprecedented scientific commons, a marketplace of ideas in which Ferguson’s arguments sound only a little better than “the dog ate my homework.” Worst of all, however, Ferguson and Imperial College, through both their work and their haughtiness about it, have put the public at risk. Epidemiological modelling is a valuable tool for public health, and Covid-19 underscores the value of such models in decision-making. But the Imperial College model implementation lends credence to the worst fears of modelling skeptics—namely, that many models are no better than high-stakes gambles played on computers. This isn’t true: well-executed models can contribute to the objective, data-driven decision-making that we should expect from our leaders in a crisis. But leaders need to learn how to vet models and data.

The first step toward integrating predictive models into evidence-based policy is thorough assessment of the models’ assumptions and implementation. Reasonable skepticism about predictive models is not unscientific—and blind trust in an untested, shoddily written model is not scientific. As Socrates might have put it, an unexamined model is not worth trusting.

https://www.city-journal.org/coronavirus-model-driven-decision-making

Interesting article in regards to how the British response changed so quickly. Of course I'm no expert on these things but the guy who wrote it seems like he may know a thing or two.

"Chris von Csefalvay is an epidemiologist specializing in bat-borne viruses. He is currently VP of Special Projects at Starschema."

Interesting...

I would say that all of this computer modelling predictions are totally flawed for the simple reason that it was all based on the assumption that the virus didn't arrive here in UK until early February, and first transmission within the UK was believed to be near the end of February...

But the virus has been going around here in UK since before Christmas!

I dont know if they are flawed. Neither does anyone else, because the methodology has not been released for peer review.

No one on this forum is the peer of the folks doing the study either. But everyone would benefit from more peer review.

Maddog- The newsfix Queen

- Posts : 12532

Join date : 2017-09-23

Location : Texas

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Of course they should be honest and open with releasing the data and methodology of their advice...

Tommy Monk- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 26319

Join date : 2014-02-12

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

we dont need that model to tell us what would have happened...just watch South america.......

Victorismyhero- INTERNAL SECURITY DIRECTOR

- Posts : 11441

Join date : 2015-11-06

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Tommy Monk wrote:

Of course they should be honest and open with releasing the data and methodology of their advice...

That's what keeps everyone honest.

Science is about openness, review, trial and error.

This looks political, which is sorta the opposite.

Maddog- The newsfix Queen

- Posts : 12532

Join date : 2017-09-23

Location : Texas

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Maddog wrote:Tommy Monk wrote:

Of course they should be honest and open with releasing the data and methodology of their advice...

That's what keeps everyone honest.

Science is about openness, review, trial and error.

This looks political, which is sorta the opposite.

Or economics, made political by a capitalist agenda to deceive people into going back to work despite the dangers.

It's a minor blip in the mix, unduly emphasized because it has the effect of being critical of the scientific establishment. Reality is caving in. It is the last pathetic straw that conservatives can grasp before the world recognizes their total incompetence.

Original Quill- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 37540

Join date : 2013-12-19

Age : 59

Location : Northern California

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

n the history of expensive software mistakes, Mariner 1 was probably the most notorious. The unmanned spacecraft was destroyed seconds after launch from Cape Canaveral in 1962 when it veered dangerously off-course due to a line of dodgy code.

But nobody died and the only hits were to Nasa’s budget and pride. Imperial College’s modelling of non-pharmaceutical interventions for Covid-19 which helped persuade the UK and other countries to bring in draconian lockdowns will supersede the failed Venus space probe and could go down in history as the most devastating software mistake of all time, in terms of economic costs and lives lost.

Since publication of Imperial’s microsimulation model, those of us with a professional and personal interest in software development have studied the code on which policymakers based their fateful decision to mothball our multi-trillion pound economy and plunge millions of people into poverty and hardship. And we were profoundly disturbed at what we discovered. The model appears to be totally unreliable and you...

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2020/05/16/neil-fergusons-imperial-model-could-devastating-software-mistake/

But nobody died and the only hits were to Nasa’s budget and pride. Imperial College’s modelling of non-pharmaceutical interventions for Covid-19 which helped persuade the UK and other countries to bring in draconian lockdowns will supersede the failed Venus space probe and could go down in history as the most devastating software mistake of all time, in terms of economic costs and lives lost.

Since publication of Imperial’s microsimulation model, those of us with a professional and personal interest in software development have studied the code on which policymakers based their fateful decision to mothball our multi-trillion pound economy and plunge millions of people into poverty and hardship. And we were profoundly disturbed at what we discovered. The model appears to be totally unreliable and you...

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2020/05/16/neil-fergusons-imperial-model-could-devastating-software-mistake/

Maddog- The newsfix Queen

- Posts : 12532

Join date : 2017-09-23

Location : Texas

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

yeah, like I said...lets do nothing, like South America...thats going well innit?

Victorismyhero- INTERNAL SECURITY DIRECTOR

- Posts : 11441

Join date : 2015-11-06

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Victorismyhero wrote:yeah, like I said...lets do nothing, like South America...thats going well innit?

It's much ado about nothing. Comparing a methodological quibble to a downed NASA flight is like Chicken Little screaming, the sky is falling, the sky is falling!

Original Quill- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 37540

Join date : 2013-12-19

Age : 59

Location : Northern California

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Victorismyhero wrote:yeah, like I said...lets do nothing, like South America...thats going well innit?

Or do something based on flawed modeling. What a great idea.

Maddog- The newsfix Queen

- Posts : 12532

Join date : 2017-09-23

Location : Texas

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Maddog wrote:Victorismyhero wrote:yeah, like I said...lets do nothing, like South America...thats going well innit?

Or do something based on flawed modeling. What a great idea.

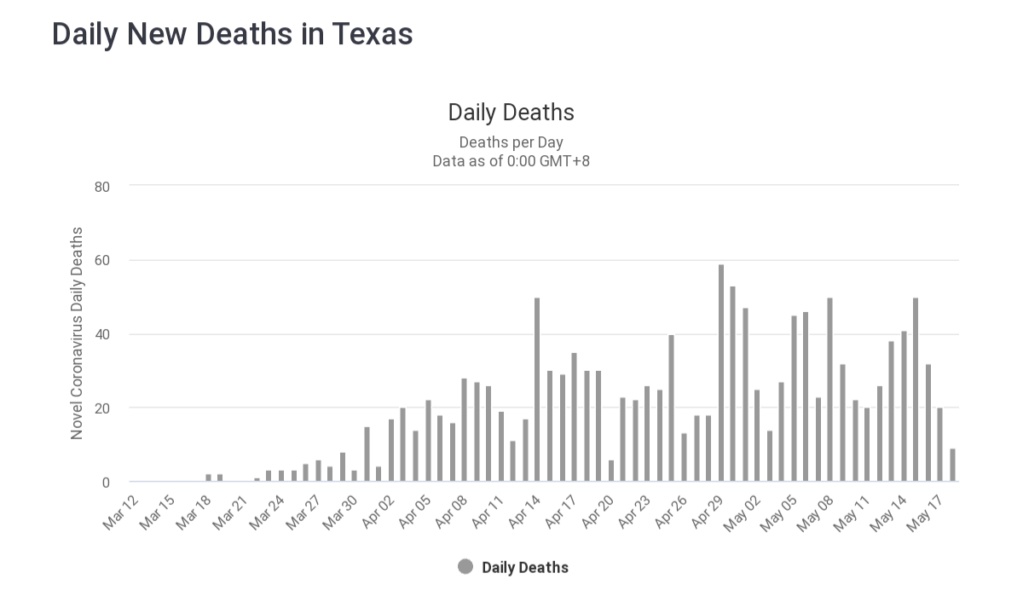

Like extend the distancing and protection/lockdown measures, in the absence of any reason to do otherwise. Deaths rising in Texas, in particular.

Original Quill- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 37540

Join date : 2013-12-19

Age : 59

Location : Northern California

Maddog- The newsfix Queen

- Posts : 12532

Join date : 2017-09-23

Location : Texas

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Re: Blind trust in scientific authorities, written by a scientist.

Good luck with the reopening, Texas.

Original Quill- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 37540

Join date : 2013-12-19

Age : 59

Location : Northern California

Similar topics

Similar topics» 'Blind Trust Project' Seeks To Inspire Trust Of Muslims Everywhere

» Which News broadcasters do you trust or not trust....

» Do you trust trust female pilots

» Some Songs Were Written For Ben And Eddie

» Hexes & Curses

» Which News broadcasters do you trust or not trust....

» Do you trust trust female pilots

» Some Songs Were Written For Ben And Eddie

» Hexes & Curses

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

» TOTAL MADNESS Great British Railway Journeys among shows flagged by counter terror scheme ‘for encouraging far-right sympathies

» Interesting COVID figures

» HAPPY CHRISTMAS.

» The Fight Over Climate Change is Over (The Greenies Won!)

» Trump supporter murders wife, kills family dog, shoots daughter

» Quill

» Algerian Woman under investigation for torture and murder of French girl, 12, whose body was found in plastic case in Paris

» Wind turbines cool down the Earth (edited with better video link)

» Saying goodbye to our Queen.

» PHEW.

» And here's some more enrichment...

» John F Kennedy Assassination

» Where is everyone lately...?

» London violence over the weekend...

» Why should anyone believe anything that Mo Farah says...!?

» Liverpool Labour defends mayor role poll after turnout was only 3% and they say they will push ahead with the option that was least preferred!!!

» Labour leader Keir Stammer can't answer the simple question of whether a woman has a penis or not...

» More evidence of remoaners still trying to overturn Brexit... and this is a conservative MP who should be drummed out of the party and out of parliament!

» R Kelly 30 years, Ghislaine Maxwell 20 years... but here in UK...