Saving Lives on the Front Line

2 posters

Page 1 of 1

Saving Lives on the Front Line

Saving Lives on the Front Line

The work of military nurses at Passchendaele transformed the perception of women’s war service, showing they could perform life-saving work and risk their lives at the front.

In the summer of 1917, hundreds of military nurses were moved from base hospitals on the north coast of France to casualty clearing stations (CCSs) and field hospitals in Flanders. Travelling through French and Belgian farmlands, many noted in their diaries how beautiful the fields were in June and early July, full of flowering poppies, marguerites and cornflowers. Yet the further east they journeyed, the more powerfully the First World War – the war they believed would end all wars – forced itself upon their consciousness. The roads were choked with tens of thousands of soldiers making their way to the front, jockeying for space with horse-drawn artillery limbers and wagons filled with ammunition. While still many miles from the front, they could hear the distant thunder of the bombardment – part of the escalation of warfare in the days leading up to the Third Battle of Ypres. On arriving at Brandhoek, where the CCSs were only three miles from the reserve trenches, Australian nurse May Tilton noted in her diary that:

Most CCSs were clustered in a small area just west of the ruined Belgian city of Ypres, close to a devastated terrain over which two lengthy – and inconclusive – campaigns had already been fought. In October 1914, the First Battle of Ypres had fixed the shape of the Ypres Salient, a bulge of land pushing eastwards from the city itself. For the next three years, the German army had dominated the high ground to the north, east and south of Ypres and its officers had been able to observe the movement of Allied troops and armaments. In April 1915, in the Second Battle of Ypres, poison gas had been used for the first time during a German attempt to break through the Allied lines. Approximately 1,000 French and North African troops were killed instantly. Many thousands more had been brought, coughing, choking and temporarily blinded, to casualty clearing stations and field hospitals to the west of Ypres. Now, two years later, in the summer of 1917, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig was planning ‘Third Ypres’, the ‘breakthrough’ that would win – and end – the war.

Until the First World War, women who ‘followed’ armies and cared for their wounded had been viewed with suspicion. Even the creation in 1902 of the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) during the Second Anglo-Boer War had permitted female nurses only a minor presence in the bastion of patriarchal authority that was known, from 1898 onwards, as the Royal Army Medical Corps. But the position of women was already changing as the campaign to secure women’s right to vote progressed. In 1908 a Territorial Force Nursing Service had created a register of approximately 3,000 female nurses willing to enrol in military hospital service on the home front in time of war. The QAIMNS had a reserve of about 800 members, ready to serve overseas should war be declared. A year later, units known as ‘Voluntary Aid Detachments’ were formed and these recruited more than 70,000 volunteer nurses.

The ‘official’ British military nursing units had mobilised for service on the Western Front in August 1914 but, during the early months of the war, military hospitals were slow to recruit fully trained female nurses, leaving many frustrated professionals searching for other opportunities to support the Allied war effort. As a result, many British and American nurses offered their services to small volunteer hospitals working under the auspices of the French and Belgian Societies of the Red Cross. Violetta Thurstan, a professional nurse who had trained at the London Hospital at the turn of the century, had led a unit of nurses to Brussels in September, only to be taken prisoner by the rapidly advancing German army and transported, along with about 100 other nurses, to neutral Denmark. Following a period of service on the Eastern Front, working under the auspices of the Russian Red Cross and performing both military and humanitarian relief work, Thurstan was appointed matron of the largest Belgian base hospital on the Western Front, L’Hôpital de l’Océan at La Panne on the North Sea coast.

One of the best-known volunteer units – and a hospital that was highly celebrated in its own time – was ‘Chirurgical Mobile No. 1’, or ‘Mobile Surgical No. 1’, which was funded and directed by Mary Borden Turner, a millionaire from Chicago. The hospital had been established in the summer of 1915 in the small village of Beveren, a mile from the Belgian/French border, on the road along which many troops marched towards their front-line positions just north of Ypres. It was a remarkably international unit, with nurses from France, Britain, the US, Australia and Canada. Its doctors and orderlies – or infirmiers – were all French, but the funding and supply of the unit, along with the deployment and direction of its nursing staff, was entirely under the control of Borden herself. Because she had little direct experience of nursing work, Borden had taken on a highly trained head nurse, Agnes Warner, a Canadian citizen and graduate of the Presbyterian Hospital of New York.

International effort

Many Australian and New Zealand nurses arrived on the Western Front in the winter of 1915/16, having spent several gruelling months caring for the wounded of the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign in base hospitals in Egypt and on the Greek island of Lemnos. Many had been posted to hospital ships moving between the Gallipoli peninsula and the bases at Egypt, Lemnos and Malta. Others had been sent to the Greek port of Salonika to care for the wounded of the Serbian and Macedonian campaigns. Following their redeployment to France, many were posted to British CCSs, until units staffed and organised by their own medical services were ready to move up to the front lines. Canadian nurses were also being deployed in greater numbers to the northern sectors of the Western Front.

In April 1917, when the US entered the war, American ‘base hospitals’ were mobilised rapidly. Many had been working quietly to build war-ready units of doctors, nurses and orderlies for about a year. One of the first to depart for Europe, in May 1917, was US Base Hospital No. 10, also known as the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit. Among its nurses was newly qualified Helen Fairchild, who had given up a job as a visiting nurse on Long Island in order to return to her training hospital’s war unit, despite the fact that she was suffering from an undiagnosed stomach ulcer and was not really fit for travel to a warzone. Base Hospital No. 10, along with others travelling to France that spring, would care for British and Dominion troops until their own countrymen became involved in the war the following summer.

During the first two years of war, the Western Front had become increasingly entrenched, looking almost as though it could become a permanent feature on the landscape, extending for about 450 miles, from the North Sea to the Swiss border. But the static nature of the front permitted the creation of highly sophisticated lines of evacuation, which stretched, unbroken, from the front lines in Belgium and eastern France to bases such as Étaples and Boulogne on the north coast of France, and then across the English Channel to general hospitals in Britain. Strategically placed along these lines were regimental aid posts, advanced dressing stations, CCSs, stationary hospitals and base hospitals. Conveying the wounded from one treatment scenario to another were motor ambulances, ambulance trains and barges.

The most challenging work took place at CCSs. When patients arrived – often in ‘rushes’ of several hundred at a time – nurses got to work quickly, countering the wound-shock and hypothermia from which many were suffering. Most patients had severe, infected wounds and nurses knew that their immediate survival depended on their ‘rescue’ from the effects of those wounds. One nurse referred to shock-therapy as a process of ‘reviving the cold dead’, while others commented in their memoirs that combatting shock was like drawing men back from the brink of an abyss.

Extreme measures

Once men’s shock had been reversed, nurses turned their attention to preparing them for surgery. The wounds sustained on the muddy battlefields of Flanders were heavily contaminated with anaerobic bacteria, causing devastating and life-threatening diseases, such as gas gangrene and tetanus. Surgeons learned, in the earliest months of the war, that the best way to combat such infections was to remove vast swathes of contaminated tissue from within and around the wound, cutting well into the neighbouring healthy tissues in order to be certain that the infections had been eradicated. The surgery deepened patients’ trauma. Following each patient’s return from the operating theatre, nurses worked laboriously to heal his wounds and rebuild his strength and health. Once patients had recovered sufficiently to survive the journey, they were loaded onto ambulance trains and their treatment and care were handed over to transport nurses.

There were two elements to the surgical work of CCS nurses: the healing of war wounds required some highly technical expertise, while fundamental caring skills were needed to restore men to health. The mobilisation of skills such as the antiseptic treatment and aseptic dressing of complex and painful wounds went hand-in-hand with the washing, feeding and toileting of sometimes helpless patients. The First World War saw innovations such as ‘Carrel-Dakin wound irrigation’, a method for delivering the antiseptic solution, sodium hypochlorite, into deep wounds, along with increasingly sophisticated shock therapies, which included new approaches to blood transfusion. The work was relentless. Nurses were responsible for observing their patients closely and monitoring them for any signs of complications, as well as for delivering a range of treatments. The Irish nurse Catherine Black summed up their feelings when she wrote in her memoir, King’s Nurse – Beggar’s Nurse:

The zone of the armies

Bringing hospitals as close as possible to the place where men were wounded reduced the time it took to transfer those men from battlefield to operating theatre. If a patient could reach a hospital – even a small, makeshift field hospital – within six hours of his wounding, clinical staff would have a chance of eradicating the galloping infections in his wounds and of saving his life. But for nurses who were unaccustomed to warfare, the experience of serving in the ‘zone of the armies’ was, at some times, strange and extraordinary, at others, terrifying. The later battles of the Third Ypres Campaign, including the struggles to capture Broodseinde, Poelcapelle and Passchendaele, which took place in October and November 1917, were among the most distressing times for nurses in CCSs and field hospitals. May Tilton commented in her book,

The Grey Battalion:

We hated and dreaded the days that followed this incessant thundering [of the initial bombardment], when the torn, bleeding and pitifully broken human beings were brought in, their eyes filled with horror and pain; those who could walk staggering dumbly, pitifully, in the wrong direction. Days later men were carried in who had been found lying in shell holes, starved, cold, and pulseless, but, by some miracle, still alive. Many died of exposure and the dreadedgas gangrene.

A very novel experience

In August 1917, several surgical teams, each consisting of a medical officer, a nursing sister, an anaesthetist and an orderly, were sent out to CCSs from base hospitals on the French coast. Among them were teams from the No. 10 US Base Hospital at Le Treport. Helen Fairchild was one of those who volunteered for front-line service. On 13 August 1917, she wrote to her mother:

I am out with an operating team.

We are about 100 miles away from our own hospital, close to the fighting lines, and I surely will have lots to tell you about this experience when I get home. We have been up here three weeks and see no signs of going back yet, although when we came we only expected to be here a few days; so, of course, we didn’t bring much with us. I had two white dresses and two aprons and two combinations. Now can you imagine trying to keep decent looking for three weeks with that much clothing, in a place where it rains nearly every day, and we live in tents, and wade through mud to and from the operating room. It was some task, but finally dear old Major Harte, who I am up here with, got a car and a man to go down to our own hospital and get us some things … This has been a very novel experience, but I will be glad when we get orders to go back … Oh, I shall have books to tell you all when I get home … Heaps and heaps of love to you one and all, your very own Helen.

In August the bombing intensified.

Violetta Thurstan, who had transferred from L’Hôpital de l’Océan to a British advanced dressing station at Coxyde, very close to the northernmost sector of the front lines, was injured during the bombing of a makeshift operating theatre. She was later awarded the Military Medal, the highest military accolade that could then be given to a woman. Her citation, quoted by the historian Norman Gooding in his Honours and Awards to Women, stated that:

She dragged a wounded man into a shelter at great personal risk and afterwards she assisted at an operation and in dressing the wounded though at the time the shelling was very heavy and part of the hut in which the dressings were being performed was struck by a shell. She was herself hit on the head and dazed by a piece of falling timber. Nevertheless, she continued to work and assist in the evacuation of the helpless wounded – a most stimulating example to all. When removed to the Casualty Clearing Station she protested at being detained there and expressed an urgent desire to return to the Corps Main Dressing Station.

John Gibbon, an orderly with US Base Hospital No. 10, who had travelled to British CCS No. 4 as part of a surgical team, contributed to a History of the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit, edited by his former colleague, Paul Hoeber. He commented on the courage of the nursing sisters at the CCS:

Night bombing is a terrifying thing and those who are not disturbed by it possess unusual qualities. It was terrifying to Tommies and officers alike, but I believe that the women nurses showed less fear than any one. Our own nurse, Miss Gerhart, really seemed to enjoy her experience and I think was the only one who had any regret at leaving No. 61. She was always cheerful and always working. She was liked by the British, both men and women, who at first called her ‘The American Sister’, but later spoke of her less respectfully, but more affectionately as Cat-Gut-Katie.

In late July 1917, three CCSs – Nos. 32 and 44 British and No. 3 Australian – had been combined to create a large complex of hospitals at Brandhoek, just three miles from the front lines at Ypres. This ‘Advanced Abdominal Centre’ specialised in three of the most dangerous forms of wounds: injuries to the abdomen and/or chest and fractures to the femur. The military medical services had determined that these particularly urgent cases were more likely to be saved, if they could reach an operating theatre within three hours of their wounding. Nurses were moved ‘up the line’ to the Advanced Abdominal Centre in the last week of July and were placed under the command of highly experienced Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (Reserve) Sister, Kate Luard. Supporting her were the sisters-in-charge of No. 44 British CCS and No. 3 Australian, Minnie Wood and Ida O’Dwyer.

The three CCSs were located close to railheads to enable their staff to transfer patients more easily to ambulance trains. But their proximity to such strategic locations meant that shells from long-range artillery and bombs from air raids often landed very close to their compounds. On 21 August 1917, the complex took a direct hit, a shell landing very close to the sisters’ quarters at No. 44. Staff nurse Nellie Spindler, a 26-year-old from Wakefield in West Yorkshire, was hit by a piece of shrapnel as she lay sleeping in her tent. She died 20 minutes later in the arms of her sister-in-charge, Minnie Wood. Nurses and patients were evacuated from the hospital and were moved west to the small French town of Saint-Omer, where Wood wrote a poignant letter to Nellie’s parents:

Before you receive this letter I expect you have heard of your great loss. I don’t know what to say to you, for I cannot express my feelings in writing, and no words of mine can soften the blow. There is one consolation for you; your daughter became unconscious immediately after she was hit, and she passed away perfectly peacefully at 11.20am – just twenty minutes afterwards. I was with her at the time, but [after] the first minute or two she did not know me. It was a great mercy she was oblivious to her surroundings, for the shells continued to fall in for the rest of the day.

Greater danger

It was around this time that Helen Fairchild returned to US Base Hospital No. 10. Her health remained fragile and by Christmas she was vomiting after every meal and was advised to undergo surgery to remove a large stomach ulcer. In January 1918, the surgery was performed at Canadian Stationary Hospital No. 3. Helen died on 18 January of ‘acute yellow atrophy of the liver’. Her family was told later, by one of her colleagues, that her ulcer had been worsened by exposure to mustard gas during her time at No. 4 British CCS near Westvleteren. It was also said that she had given her own gas mask to a patient, thereby exposing herself to greater danger.

Many female nurses were awarded medals in recognition of their services during the Third Ypres campaign. Some senior members of the official services received the Royal Red Cross for distinguished service; others were granted the Military Medal; some received both. Mary Borden, serving the French Service de Santé des Armées, was awarded the Médaille des Epidemies and the Croix de Guerre with two palms.

On 6 February 1918, Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act, granting women over 30 the right to vote in future elections and, on 23 December 1919, it passed the Nurses Registration Act: British nurses joined their colleagues in New Zealand and in some US and Australian states in being granted legal professional status. By the time they gained these limited but legally sanctioned rights, women and nurses had been campaigning for over five decades. It is impossible to gauge the extent to which their service on the front lines of war convinced their government to recognise their status as both citizens and professionals. But the widespread admiration their work evoked can only have helped their campaigns for legal recognition.

Christine E. Hallett is Professor of Nursing History at the University of Manchester. She is the author of Nurses of Passchendaele: Caring for the Wounded of the Ypres Campaigns (Pen and Sword Books, 2017).

https://www.historytoday.com/christine-e-hallett/saving-lives-front-line

In the summer of 1917, hundreds of military nurses were moved from base hospitals on the north coast of France to casualty clearing stations (CCSs) and field hospitals in Flanders. Travelling through French and Belgian farmlands, many noted in their diaries how beautiful the fields were in June and early July, full of flowering poppies, marguerites and cornflowers. Yet the further east they journeyed, the more powerfully the First World War – the war they believed would end all wars – forced itself upon their consciousness. The roads were choked with tens of thousands of soldiers making their way to the front, jockeying for space with horse-drawn artillery limbers and wagons filled with ammunition. While still many miles from the front, they could hear the distant thunder of the bombardment – part of the escalation of warfare in the days leading up to the Third Battle of Ypres. On arriving at Brandhoek, where the CCSs were only three miles from the reserve trenches, Australian nurse May Tilton noted in her diary that:

The flashes from the guns and the marvellous illuminations in the sky [were] more dazzling than any lightning.

A continuous rumble and roar, as of an immense factory of vibrating machinery, filled the night. The pulsings and vibration worked into our bodies and brains; the screech of big shells, and the awful crash when they burst at no great distance, kept our nerves on edge; but even to this terrific noise we became accustomed.

Most CCSs were clustered in a small area just west of the ruined Belgian city of Ypres, close to a devastated terrain over which two lengthy – and inconclusive – campaigns had already been fought. In October 1914, the First Battle of Ypres had fixed the shape of the Ypres Salient, a bulge of land pushing eastwards from the city itself. For the next three years, the German army had dominated the high ground to the north, east and south of Ypres and its officers had been able to observe the movement of Allied troops and armaments. In April 1915, in the Second Battle of Ypres, poison gas had been used for the first time during a German attempt to break through the Allied lines. Approximately 1,000 French and North African troops were killed instantly. Many thousands more had been brought, coughing, choking and temporarily blinded, to casualty clearing stations and field hospitals to the west of Ypres. Now, two years later, in the summer of 1917, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig was planning ‘Third Ypres’, the ‘breakthrough’ that would win – and end – the war.

Until the First World War, women who ‘followed’ armies and cared for their wounded had been viewed with suspicion. Even the creation in 1902 of the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) during the Second Anglo-Boer War had permitted female nurses only a minor presence in the bastion of patriarchal authority that was known, from 1898 onwards, as the Royal Army Medical Corps. But the position of women was already changing as the campaign to secure women’s right to vote progressed. In 1908 a Territorial Force Nursing Service had created a register of approximately 3,000 female nurses willing to enrol in military hospital service on the home front in time of war. The QAIMNS had a reserve of about 800 members, ready to serve overseas should war be declared. A year later, units known as ‘Voluntary Aid Detachments’ were formed and these recruited more than 70,000 volunteer nurses.

The ‘official’ British military nursing units had mobilised for service on the Western Front in August 1914 but, during the early months of the war, military hospitals were slow to recruit fully trained female nurses, leaving many frustrated professionals searching for other opportunities to support the Allied war effort. As a result, many British and American nurses offered their services to small volunteer hospitals working under the auspices of the French and Belgian Societies of the Red Cross. Violetta Thurstan, a professional nurse who had trained at the London Hospital at the turn of the century, had led a unit of nurses to Brussels in September, only to be taken prisoner by the rapidly advancing German army and transported, along with about 100 other nurses, to neutral Denmark. Following a period of service on the Eastern Front, working under the auspices of the Russian Red Cross and performing both military and humanitarian relief work, Thurstan was appointed matron of the largest Belgian base hospital on the Western Front, L’Hôpital de l’Océan at La Panne on the North Sea coast.

One of the best-known volunteer units – and a hospital that was highly celebrated in its own time – was ‘Chirurgical Mobile No. 1’, or ‘Mobile Surgical No. 1’, which was funded and directed by Mary Borden Turner, a millionaire from Chicago. The hospital had been established in the summer of 1915 in the small village of Beveren, a mile from the Belgian/French border, on the road along which many troops marched towards their front-line positions just north of Ypres. It was a remarkably international unit, with nurses from France, Britain, the US, Australia and Canada. Its doctors and orderlies – or infirmiers – were all French, but the funding and supply of the unit, along with the deployment and direction of its nursing staff, was entirely under the control of Borden herself. Because she had little direct experience of nursing work, Borden had taken on a highly trained head nurse, Agnes Warner, a Canadian citizen and graduate of the Presbyterian Hospital of New York.

International effort

Staff nurse Nellie Spindler. Courtesy the Lijssenthoek Cemetery Visitor Centre.

Many Australian and New Zealand nurses arrived on the Western Front in the winter of 1915/16, having spent several gruelling months caring for the wounded of the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign in base hospitals in Egypt and on the Greek island of Lemnos. Many had been posted to hospital ships moving between the Gallipoli peninsula and the bases at Egypt, Lemnos and Malta. Others had been sent to the Greek port of Salonika to care for the wounded of the Serbian and Macedonian campaigns. Following their redeployment to France, many were posted to British CCSs, until units staffed and organised by their own medical services were ready to move up to the front lines. Canadian nurses were also being deployed in greater numbers to the northern sectors of the Western Front.

In April 1917, when the US entered the war, American ‘base hospitals’ were mobilised rapidly. Many had been working quietly to build war-ready units of doctors, nurses and orderlies for about a year. One of the first to depart for Europe, in May 1917, was US Base Hospital No. 10, also known as the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit. Among its nurses was newly qualified Helen Fairchild, who had given up a job as a visiting nurse on Long Island in order to return to her training hospital’s war unit, despite the fact that she was suffering from an undiagnosed stomach ulcer and was not really fit for travel to a warzone. Base Hospital No. 10, along with others travelling to France that spring, would care for British and Dominion troops until their own countrymen became involved in the war the following summer.

During the first two years of war, the Western Front had become increasingly entrenched, looking almost as though it could become a permanent feature on the landscape, extending for about 450 miles, from the North Sea to the Swiss border. But the static nature of the front permitted the creation of highly sophisticated lines of evacuation, which stretched, unbroken, from the front lines in Belgium and eastern France to bases such as Étaples and Boulogne on the north coast of France, and then across the English Channel to general hospitals in Britain. Strategically placed along these lines were regimental aid posts, advanced dressing stations, CCSs, stationary hospitals and base hospitals. Conveying the wounded from one treatment scenario to another were motor ambulances, ambulance trains and barges.

The most challenging work took place at CCSs. When patients arrived – often in ‘rushes’ of several hundred at a time – nurses got to work quickly, countering the wound-shock and hypothermia from which many were suffering. Most patients had severe, infected wounds and nurses knew that their immediate survival depended on their ‘rescue’ from the effects of those wounds. One nurse referred to shock-therapy as a process of ‘reviving the cold dead’, while others commented in their memoirs that combatting shock was like drawing men back from the brink of an abyss.

Extreme measures

Once men’s shock had been reversed, nurses turned their attention to preparing them for surgery. The wounds sustained on the muddy battlefields of Flanders were heavily contaminated with anaerobic bacteria, causing devastating and life-threatening diseases, such as gas gangrene and tetanus. Surgeons learned, in the earliest months of the war, that the best way to combat such infections was to remove vast swathes of contaminated tissue from within and around the wound, cutting well into the neighbouring healthy tissues in order to be certain that the infections had been eradicated. The surgery deepened patients’ trauma. Following each patient’s return from the operating theatre, nurses worked laboriously to heal his wounds and rebuild his strength and health. Once patients had recovered sufficiently to survive the journey, they were loaded onto ambulance trains and their treatment and care were handed over to transport nurses.

There were two elements to the surgical work of CCS nurses: the healing of war wounds required some highly technical expertise, while fundamental caring skills were needed to restore men to health. The mobilisation of skills such as the antiseptic treatment and aseptic dressing of complex and painful wounds went hand-in-hand with the washing, feeding and toileting of sometimes helpless patients. The First World War saw innovations such as ‘Carrel-Dakin wound irrigation’, a method for delivering the antiseptic solution, sodium hypochlorite, into deep wounds, along with increasingly sophisticated shock therapies, which included new approaches to blood transfusion. The work was relentless. Nurses were responsible for observing their patients closely and monitoring them for any signs of complications, as well as for delivering a range of treatments. The Irish nurse Catherine Black summed up their feelings when she wrote in her memoir, King’s Nurse – Beggar’s Nurse:

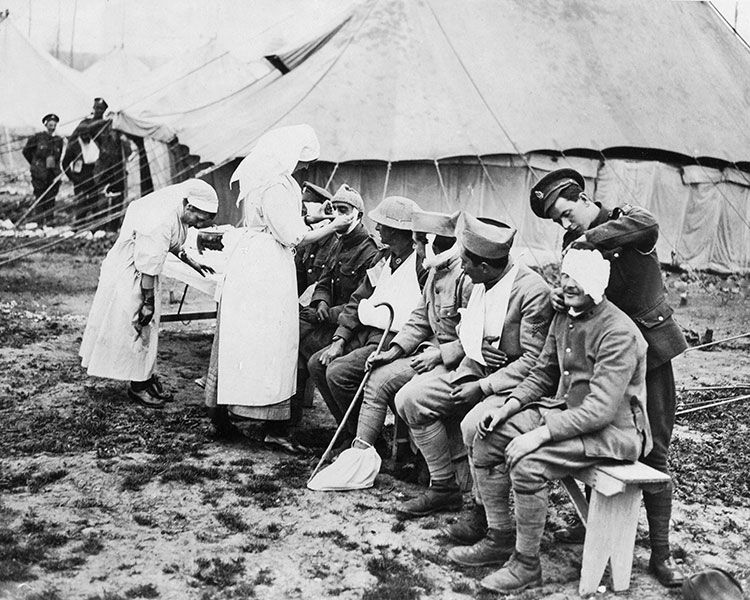

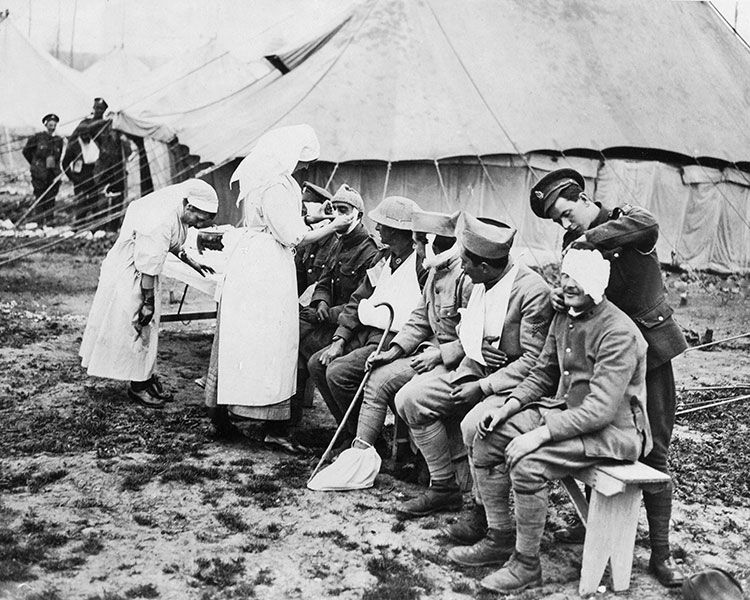

Hilda Loxton, an Australian Red Cross ‘bluebird’ working at Mobile Surgical No. 1, kept a detailed diary of her work, which is now preserved at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. In September, she wrote about the battle to save the life of one of her patients:You could not go through the things we went through, see the things we saw, and remain the same. You went into it young and light-hearted. You came out older than any span of years could make you. But at the time you did not reflect on it much, or on anything else. You did not dare to. Instead you filled your mind with concrete facts – pulses and temperatures, dressings and treatments – because you soon learned that if you concentrated hard enough on them it stopped you remembering other things.Patients and nurses at the French field hospital Mobile Surgical No. 1. Reproduced by kind permission of the Provincial Archives of Alberta (PR1986.0054/0012.0001)

I had one little boy admitted … He had a large back wound, the éclat [shell fragment] entering the lower part of the back passed the diaphragm, a part of the liver, and lodged in one lung. He was very ill from the beginning. The piece of éclatwas extracted by Dr. de Parthenay, and he was put on Dakins treatment. His back wound was stitched up but had to be reopened again and he had several chest operations, but he steadily became worse, would not eat and was always miserable, developed kidney trouble and infective rheumatism; arms and legs swelled up to twice their size. Dr said he was dying from septicaemia, so de Parthenay tried a new treatment for him, injections of Peptone intramuscularly. He showed signs of improvement at once and after several injections made steady progress towards recovery, had a splendid appetite and became quite fat. After staying with us for about 3 months he was discharged walking and cured. He was only 19 years and very frightened that if he got better he would be sent back to the trenches again, but the Dr. said he would not be fit for a long time for that.

The zone of the armies

Bringing hospitals as close as possible to the place where men were wounded reduced the time it took to transfer those men from battlefield to operating theatre. If a patient could reach a hospital – even a small, makeshift field hospital – within six hours of his wounding, clinical staff would have a chance of eradicating the galloping infections in his wounds and of saving his life. But for nurses who were unaccustomed to warfare, the experience of serving in the ‘zone of the armies’ was, at some times, strange and extraordinary, at others, terrifying. The later battles of the Third Ypres Campaign, including the struggles to capture Broodseinde, Poelcapelle and Passchendaele, which took place in October and November 1917, were among the most distressing times for nurses in CCSs and field hospitals. May Tilton commented in her book,

The Grey Battalion:

We hated and dreaded the days that followed this incessant thundering [of the initial bombardment], when the torn, bleeding and pitifully broken human beings were brought in, their eyes filled with horror and pain; those who could walk staggering dumbly, pitifully, in the wrong direction. Days later men were carried in who had been found lying in shell holes, starved, cold, and pulseless, but, by some miracle, still alive. Many died of exposure and the dreadedgas gangrene.

A very novel experience

US Army Reserve Nurse Helen Fairchild. Courtesy Women In Military Service Museum, Arlington.

In August 1917, several surgical teams, each consisting of a medical officer, a nursing sister, an anaesthetist and an orderly, were sent out to CCSs from base hospitals on the French coast. Among them were teams from the No. 10 US Base Hospital at Le Treport. Helen Fairchild was one of those who volunteered for front-line service. On 13 August 1917, she wrote to her mother:

I am out with an operating team.

We are about 100 miles away from our own hospital, close to the fighting lines, and I surely will have lots to tell you about this experience when I get home. We have been up here three weeks and see no signs of going back yet, although when we came we only expected to be here a few days; so, of course, we didn’t bring much with us. I had two white dresses and two aprons and two combinations. Now can you imagine trying to keep decent looking for three weeks with that much clothing, in a place where it rains nearly every day, and we live in tents, and wade through mud to and from the operating room. It was some task, but finally dear old Major Harte, who I am up here with, got a car and a man to go down to our own hospital and get us some things … This has been a very novel experience, but I will be glad when we get orders to go back … Oh, I shall have books to tell you all when I get home … Heaps and heaps of love to you one and all, your very own Helen.

In August the bombing intensified.

Violetta Thurstan, who had transferred from L’Hôpital de l’Océan to a British advanced dressing station at Coxyde, very close to the northernmost sector of the front lines, was injured during the bombing of a makeshift operating theatre. She was later awarded the Military Medal, the highest military accolade that could then be given to a woman. Her citation, quoted by the historian Norman Gooding in his Honours and Awards to Women, stated that:

She dragged a wounded man into a shelter at great personal risk and afterwards she assisted at an operation and in dressing the wounded though at the time the shelling was very heavy and part of the hut in which the dressings were being performed was struck by a shell. She was herself hit on the head and dazed by a piece of falling timber. Nevertheless, she continued to work and assist in the evacuation of the helpless wounded – a most stimulating example to all. When removed to the Casualty Clearing Station she protested at being detained there and expressed an urgent desire to return to the Corps Main Dressing Station.

John Gibbon, an orderly with US Base Hospital No. 10, who had travelled to British CCS No. 4 as part of a surgical team, contributed to a History of the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit, edited by his former colleague, Paul Hoeber. He commented on the courage of the nursing sisters at the CCS:

Night bombing is a terrifying thing and those who are not disturbed by it possess unusual qualities. It was terrifying to Tommies and officers alike, but I believe that the women nurses showed less fear than any one. Our own nurse, Miss Gerhart, really seemed to enjoy her experience and I think was the only one who had any regret at leaving No. 61. She was always cheerful and always working. She was liked by the British, both men and women, who at first called her ‘The American Sister’, but later spoke of her less respectfully, but more affectionately as Cat-Gut-Katie.

In late July 1917, three CCSs – Nos. 32 and 44 British and No. 3 Australian – had been combined to create a large complex of hospitals at Brandhoek, just three miles from the front lines at Ypres. This ‘Advanced Abdominal Centre’ specialised in three of the most dangerous forms of wounds: injuries to the abdomen and/or chest and fractures to the femur. The military medical services had determined that these particularly urgent cases were more likely to be saved, if they could reach an operating theatre within three hours of their wounding. Nurses were moved ‘up the line’ to the Advanced Abdominal Centre in the last week of July and were placed under the command of highly experienced Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (Reserve) Sister, Kate Luard. Supporting her were the sisters-in-charge of No. 44 British CCS and No. 3 Australian, Minnie Wood and Ida O’Dwyer.

The three CCSs were located close to railheads to enable their staff to transfer patients more easily to ambulance trains. But their proximity to such strategic locations meant that shells from long-range artillery and bombs from air raids often landed very close to their compounds. On 21 August 1917, the complex took a direct hit, a shell landing very close to the sisters’ quarters at No. 44. Staff nurse Nellie Spindler, a 26-year-old from Wakefield in West Yorkshire, was hit by a piece of shrapnel as she lay sleeping in her tent. She died 20 minutes later in the arms of her sister-in-charge, Minnie Wood. Nurses and patients were evacuated from the hospital and were moved west to the small French town of Saint-Omer, where Wood wrote a poignant letter to Nellie’s parents:

Before you receive this letter I expect you have heard of your great loss. I don’t know what to say to you, for I cannot express my feelings in writing, and no words of mine can soften the blow. There is one consolation for you; your daughter became unconscious immediately after she was hit, and she passed away perfectly peacefully at 11.20am – just twenty minutes afterwards. I was with her at the time, but [after] the first minute or two she did not know me. It was a great mercy she was oblivious to her surroundings, for the shells continued to fall in for the rest of the day.

Greater danger

It was around this time that Helen Fairchild returned to US Base Hospital No. 10. Her health remained fragile and by Christmas she was vomiting after every meal and was advised to undergo surgery to remove a large stomach ulcer. In January 1918, the surgery was performed at Canadian Stationary Hospital No. 3. Helen died on 18 January of ‘acute yellow atrophy of the liver’. Her family was told later, by one of her colleagues, that her ulcer had been worsened by exposure to mustard gas during her time at No. 4 British CCS near Westvleteren. It was also said that she had given her own gas mask to a patient, thereby exposing herself to greater danger.

Many female nurses were awarded medals in recognition of their services during the Third Ypres campaign. Some senior members of the official services received the Royal Red Cross for distinguished service; others were granted the Military Medal; some received both. Mary Borden, serving the French Service de Santé des Armées, was awarded the Médaille des Epidemies and the Croix de Guerre with two palms.

On 6 February 1918, Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act, granting women over 30 the right to vote in future elections and, on 23 December 1919, it passed the Nurses Registration Act: British nurses joined their colleagues in New Zealand and in some US and Australian states in being granted legal professional status. By the time they gained these limited but legally sanctioned rights, women and nurses had been campaigning for over five decades. It is impossible to gauge the extent to which their service on the front lines of war convinced their government to recognise their status as both citizens and professionals. But the widespread admiration their work evoked can only have helped their campaigns for legal recognition.

Christine E. Hallett is Professor of Nursing History at the University of Manchester. She is the author of Nurses of Passchendaele: Caring for the Wounded of the Ypres Campaigns (Pen and Sword Books, 2017).

https://www.historytoday.com/christine-e-hallett/saving-lives-front-line

Guest- Guest

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

Such great women nursing brave men and boys. Such a horrifying brutal war.

magica- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 3092

Join date : 2016-08-22

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

I will read this later.x

I have been hearing people talk about what the men endured in this battle 100 years ago....unimaginable pain and suffering, so many men died by drowning in the mud that had been caused by weeks of torrential rain...we cant even imagine the horror they felt.

I have been hearing people talk about what the men endured in this battle 100 years ago....unimaginable pain and suffering, so many men died by drowning in the mud that had been caused by weeks of torrential rain...we cant even imagine the horror they felt.

Syl- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 23619

Join date : 2015-11-12

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

We can't Syl, it was a war over nothing. Millions died, and for what.

Such brave men thinking they would do their bit, such horrors they endured. We just can't comprehend what they went through.

Such brave men thinking they would do their bit, such horrors they endured. We just can't comprehend what they went through.

magica- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 3092

Join date : 2016-08-22

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

magica wrote:We can't Syl, it was a war over nothing. Millions died, and for what.

Such brave men thinking they would do their bit, such horrors they endured. We just can't comprehend what they went through.

I hate the phrase cannon fodder...but its apt. Young kids, many in their early teens, its hard to imagination the devastation felt by the families...on both sides.

Syl- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 23619

Join date : 2015-11-12

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

Re: Saving Lives on the Front Line

Yes it is Syl. It's so sad. I feel so much for their memories, their lives, their courage.

magica- Forum Detective ????♀️

- Posts : 3092

Join date : 2016-08-22

Similar topics

Similar topics» Saving Lives on the Front Line

» Young mother, 24, is shot dead in front of her fiancé after saying "all lives matter" during an argument with Black Lives Matter supporters

» Diabetes Dogs are invaluable to saving lives

» ‘Man With the Golden Arm’ is Finally Retiring After Saving the Lives of Over 2 Million Babbies

» Dying grandad refused life-saving drugs available in Scotland as he lives 9 MILES over border

» Young mother, 24, is shot dead in front of her fiancé after saying "all lives matter" during an argument with Black Lives Matter supporters

» Diabetes Dogs are invaluable to saving lives

» ‘Man With the Golden Arm’ is Finally Retiring After Saving the Lives of Over 2 Million Babbies

» Dying grandad refused life-saving drugs available in Scotland as he lives 9 MILES over border

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

» TOTAL MADNESS Great British Railway Journeys among shows flagged by counter terror scheme ‘for encouraging far-right sympathies

» Interesting COVID figures

» HAPPY CHRISTMAS.

» The Fight Over Climate Change is Over (The Greenies Won!)

» Trump supporter murders wife, kills family dog, shoots daughter

» Quill

» Algerian Woman under investigation for torture and murder of French girl, 12, whose body was found in plastic case in Paris

» Wind turbines cool down the Earth (edited with better video link)

» Saying goodbye to our Queen.

» PHEW.

» And here's some more enrichment...

» John F Kennedy Assassination

» Where is everyone lately...?

» London violence over the weekend...

» Why should anyone believe anything that Mo Farah says...!?

» Liverpool Labour defends mayor role poll after turnout was only 3% and they say they will push ahead with the option that was least preferred!!!

» Labour leader Keir Stammer can't answer the simple question of whether a woman has a penis or not...

» More evidence of remoaners still trying to overturn Brexit... and this is a conservative MP who should be drummed out of the party and out of parliament!

» R Kelly 30 years, Ghislaine Maxwell 20 years... but here in UK...